Azhdarchid Paleobiology, part III

May 28, 2008

How did we do this research?

— We looked at the environments in which azhdarchid fossils were found. Over 50% of azhdarchid fossils come from sediments that were laid down inland, suggesting that they were not a pterosaur group that often hung around near oceans and seas. Significantly, the only articulated azhdarchid fossils we have (articulated = the bones are preserved joined together as they were in life) come from inland sediments: as animal bodies fall apart rapidly after death, these articulated remains had to be buried quickly close to where the animal died to be preserved so well.

— We compared the anatomy of azhdarchid skulls and necks with those of modern birds. This showed that azhdarchids were strikingly different from mud-probers, and from animals that grab prey from the water’s surface whilst in flight.

— We assessed the flight and walking capability of the azhdarchid skeleton. Their flight apparatus was found to be similar to that of birds and bats that live inland, and their limb and foot structure was found to be among the best suited for walking of any pterosaur.

— We demonstrated that the limited range of motion possible in the azhdarchid neck was complemented by the mechanics of the limbs and long reach of the jaws. This bizarre stiff neck has previously been a problem in interpreting azhdarchid lifestyle, but in our terrestrial stalker model the long hindlimbs and skull work in unison to minimise required neck mobility and allow the animal to reach the ground with only slight bending of the neck or flexion of the forelimbs [see diagram above].

Our paper is freely available here. If you haven’t already done so, please see part I and part II for more supplementary info.

Further information can be found at Mark Witton’s flickr site and Tetrapod Zoology.

Ref – –

Azhdarchid Paleobiology, part II

May 28, 2008

The azhdarchid problem

Virtually all pterosaurs have been suggested to be shorebird-like animals; as gull- or pelican-like predators that flew over lakes and oceans, grabbig fish from the water. Azhdarchids first became reasonable well known in the 1970s, and their distinctive anatomy immediately indicated that they were not obeying this lifestyle stereotype. However, opinions on exactly what they were doing has divided pterosaur paleontologists.

Originally described as vulture-like scavengers, azhdarchids were later suggested to be mud-probers (sticking their long bills into the ground in search of prey) and, bringing azhdarchids into line with convention, subsequent paleontologists suggested that they made a living by flying over the water’s surface, grabbing fish. Other lifestyles, including wading, and aerial or aquatic predation, have been suggested too. These lifestyles are radically divergent and, in some cases, directly conflict with each other: how can an animal be specialised for probing muddy sediments in search of food and simultaneously be specialised for grabbing prey from the water surface while flying? It can’t, that’s how. What is needed for azhdarchids is for someone to sit down and carefully examine their fossils to see which lifestyle is best supported. In our new paper, we have done just this, and we propose a revolutionary new view on azhdarchid lifestyle.

Our conclusions

In contrast to the view that pterosaurs were tied to water-based lifestyles, we have found evidence that they were well adapted to a more terrestrial existence. In the new paper, we argue that azhdarchids were specialised terrestrial stalkers, walking – not flying – around ancient prairies and woodlands, grabbing small dinosaurs and other prey items with their elongate jaws. Azhdarchids were good at walking on the ground, had proportionally short but broad wings that allowed them to take off easily in inland habitats, and had long necks and skulls well suited for picking things up from the ground. Crucially, their feet were small and padded, making them adept at traversing solid ground, but unsuited for wading or swimming.

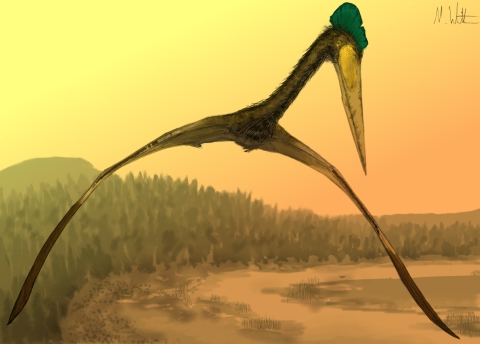

There are no giant, winged animals like azhdarchids today, but we may view large ground-feeding birds such as storks and ground hornbills as their closest modern analogues [a ground hornbill is shown in the image here]. The restoration at the top shows a group of azhdarchids (belonging to the species Quetzalcoatlus northropi) as they may have looked while foraging on a Cretaceous fern prairie (Quetzalcoatlus northropi lived in Texas during the Late Cretaceous). A juvenile titanosaur, a type of long-necked dinosaur, has been procured by one pterosaur, while the others stalk through the scrub in search of other small vertebrates.

This hypothesis is a world away from the conventional view that all pterosaurs hung around bodies of water, catching fish mid-flight or standing in the shallows searching for food. Rather, we suspect that azhdarchids were only part of a very diverse group of animals that were far more ecologically dynamic than convention suggests.

How did we do this research? To find out, please see part III….

Go here to return to part I. Our paper is freely available here. Further information can be found at Mark Witton’s flickr site and Tetrapod Zoology.

Ref – –

Azhdarchid Paleobiology, part I

May 16, 2008

Welcome to Azhdarchid Paleobiology, a blog produced to accompany the PLoS ONE paper ‘A reappraisal of azhdarchid pterosaur functional morphology and paleoecology’ by Mark P. Witton and Darren Naish (both of University of Portsmouth): this paper is freely available online here. All text and diagrams provided here should be regarded as freely available for use, but images must be credited to Mark Witton/University of Portsmouth, and cannot be used commercially.

Preamble

Pterosaurs are flying reptiles that lived during the age of the dinosaurs (between about 230 and 65 million years ago). Although often called dinosaurs, they are not part of this group and represent a distinct lineage of reptiles that evolved flight independently of birds and bats. There are around 100 species of pterosaurs currently known, and one group – including about nine species – is particularly controversial. These are the azhdarchids, a group named after the Uzbek word for ‘dragon’ [image above shows a giant azhdarchid in flight].

With massive, elongate heads, very long, stiff necks, long hindlimbs, and often gigantic size, azhdarchids are more than deserving of their ‘dragon’ title. Azhdarchids include the largest of all pterosaurs: some had wingspans exceeding 10 m and, when standing, had shoulder heights of over 2.5 m (see image below, of a 1.75 m tall human next to the biggest azhdarchid – and pterosaur – yet known, the enormous Hatzegopteryx thambema from western Romania. This pterosaur lived during the Late Cretaceous and was named and described in 2003 by Eric Buffetaut and colleagues. It is known from an incomplete skull and some arm and leg bones).

Please see part II for more…

Our paper is freely available here.

Further information can be found at Mark Witton’s flickr site and Tetrapod Zoology.

Ref – –